The work featured above is credited to Christopher Means & Max Supler.

For more information, click the “Fallout: Lonestar” banner link.

BRIEF

A small-scale, full-conversion modification to the current Fallout iteration that would develop the universe further in an area with little to no established canon. The modification would focus on narrative and the team would be comprised of industry hopefuls looking to apply skills to a larger group project. While this is certainly a team effort of talented artists, the following focuses on my contribution as Project Lead.

HISTORY

I wanted to build a small town in the Fallout universe, but every step I took established something that only made me want to establish something more. I wanted it to be in the canon-absent Texas Commonwealth to avoid conflict with any existing Fallout content. In doing this, I created a backstory vacuum that I felt compelled to fill. The more content I added, the more I became addicted to the idea of Fallout in Texas.

After attending the final GDC Online in Austin, I had a long conversation with Chris Avellone, CCO at Obsidian Entertainment and a developer on Fallout 2 and Fallout: New Vegas. Over a few beers, I pitched the idea for Fallout: Lonestar, a western-themed title set in the former Texas Commonwealth.

He liked it and told me to develop it. He also helped spread the word.

Over the following months, a team of 20+ members was assembled to begin development in the Fallout: New Vegas toolkit. Transparency and goodwill brought them to the project and remains the reason many stayed and regard the project warmly. Without funding, exposure and experience were the only commodities we had at our disposal. While exposure is frowned upon by artists, and rightly so, we were always upfront about it. Everyone involved was a volunteer whose time was considered charity. We also did our level best to showcase the work of everyone involved. I'm proud to say we've had a hand in helping members of Fallout: Lonestar achieve professional positions at studios such as BioWare, Stoic, and CD Projekt RED.

GOALS

When developing Fallout: Lonestar as a title for the Fallout universe, efforts were made to minimize contradictions with current canon and any unannounced canon that may or may not be under development by Bethesda Softworks. With this in mind, Fallout: Lonestar took advantage of the absent content regarding the former Texas Commonwealth. Texas carries a wealth of themes, styles, and concepts that complement the Fallout universe. Texas is the preeminent location of the cowboy west, and westerns mirror the post-apocalypse in nearly every regard.

American Westerns are often character-driven stories with simple plots. The best are ensemble casts with rich characters: The Magnificent Seven, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Once Upon a Time in the West. Fallout: Lonestar's goal is to keep NPCs and companions relevant as often as possible without limiting player agency.

PRODUCTION

A volunteer staff is inherently unstable in terms of consistent development. Once we decided to abandon the Fallout: New Vegas toolkit, we had time before the release of Fallout 4 to determine a proper development cycle. I laid out a system where development occurred in narrative phases. By breaking the narrative into priority phases, we could avoid stalling out and having nothing to show for our effort. Starting with the main city of Graveyard, a short, urban narrative was developed that could lead into a larger wasteland story if our manpower held out. From there, the wasteland narrative was divided by priority so we could, at all times, tell a complete story. The more manpower, the larger and more diverse the story could become.

The ONLINE STUDIO

Many platforms were tested to keep communication moving between the 20+ members in different time zones and at least six different countries. Google Drive was an easy choice for file distribution, while basic text communication proved more difficult. Forums, Trello, and just plain Skype were used, but Slack ultimately proved to be the most useful communication tool.

DEVelopment

ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN

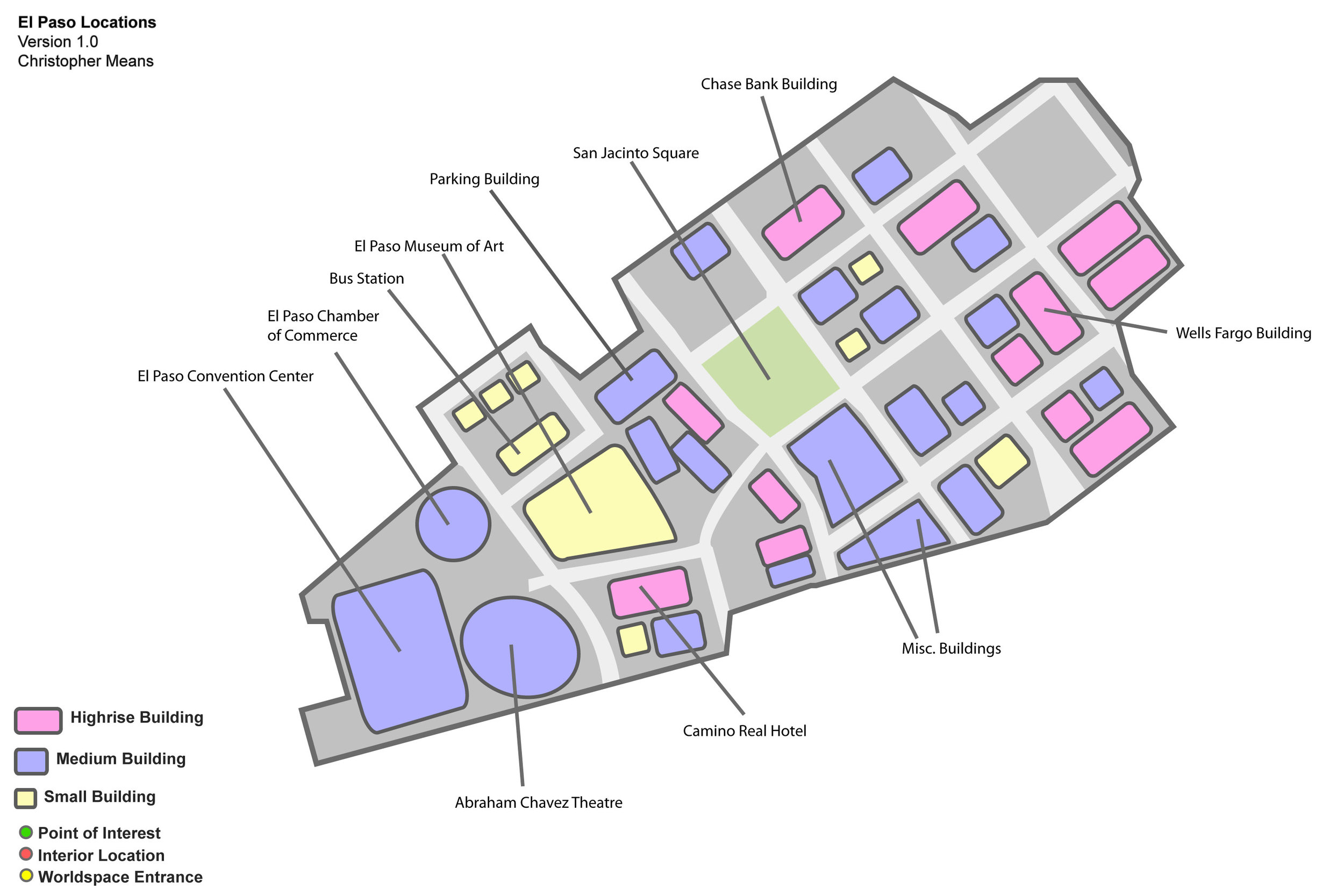

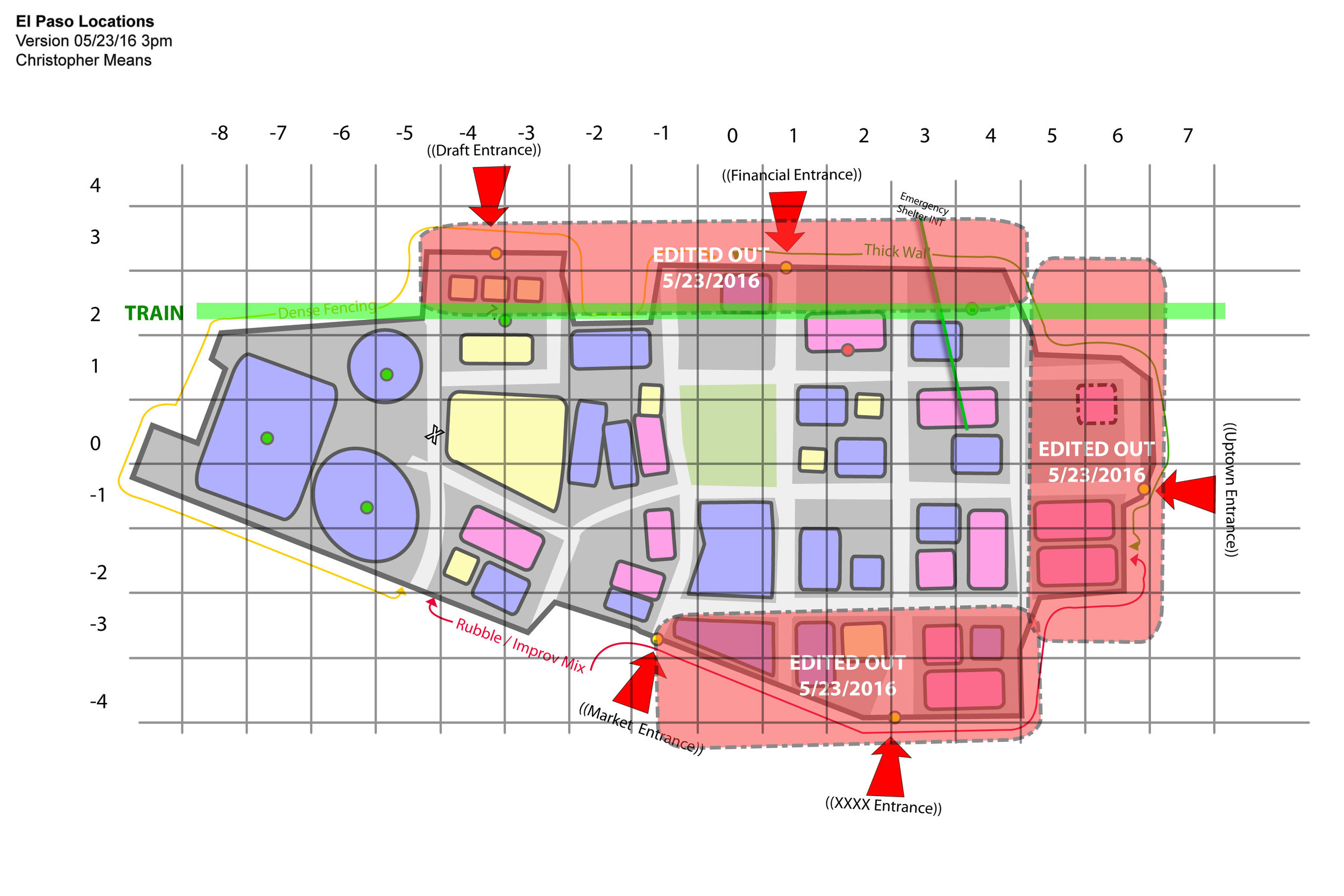

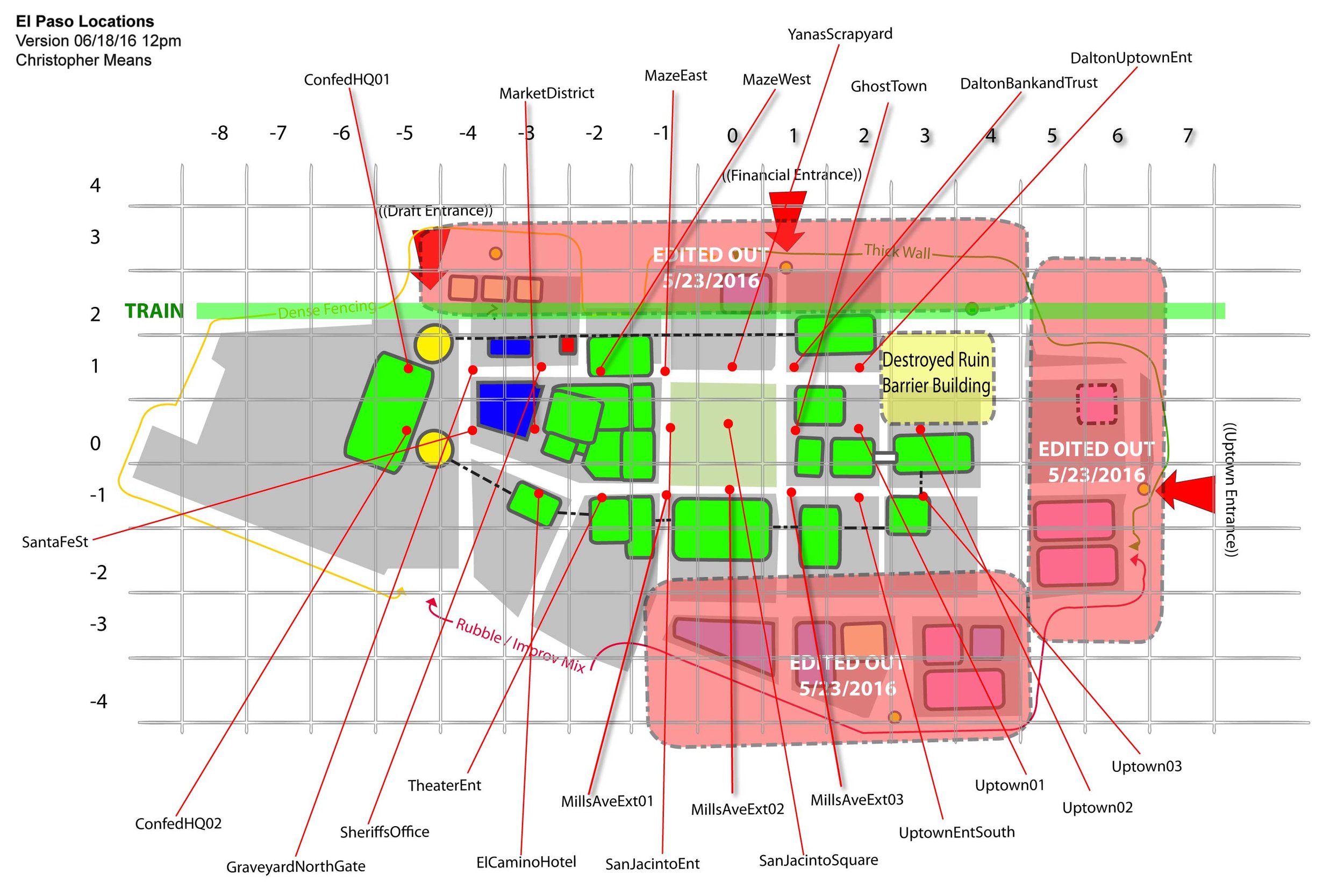

Early concept work on the Graveyard area design

After choosing El Paso as the site for Fallout: Lonestar, the city's smaller nature made further decisions rather simple. A major wasteland city would have to reside in downtown El Paso, especially if we were going to feature any of the city's landmarks. So I went to the business of carving out a place for the Lonestar's Confederacy, a city that would later be known as "Graveyard."

As a closed exterior, Graveyard was the proving ground for Fallout: Lonestar's development. A place where we could make changes, mistakes, and adjust our ambition without causing problems for the wasteland worldspace as a whole.

THE LOOK OF EL PASO

Visually distinguishing Lonestar from the Fallout 4 Commonwealth was my primary objective. When walking through Graveyard, your average Fallout fan should not feel their world is just a reshuffle of assets. I'd been able to recreate the El Paso esthetic in Fallout: Lonestar's main city of Graveyard with existing Fallout 4 assets. This was due in large part to the dynamic nature of Bethesda Softworks' Creation Kit. Assets originally intended to recreate the New England styles of post-war Boston could be rearranged into familiar southwestern shapes or completely new structures where desired.

Narrative

SETTING

The bell that tolled the end of humanity's reign was especially unkind to Texas. The great plains of the Lone Star State put up little resistance against the hellfire that burned it away. As the fallout fell, the winds changed, and the ash and sand wore down what little remained. Survivors from the great underground vaults reached the surface only to find the expanse of Texas had been swept clean of civilization. The desert before them bore little resemblance to the home glimpsed in photographs.

With the founding of the Lonestar Confederacy came the Law. While it protected many, it fed no one. Famine is dissolving Lonestar from the inside. Food is the most valuable commodity, and there are those who would use that hunger to bend the Confederacy to their will.

THEMES

WESTERNS

Several Fallout titles have explored the similarities between the Wild West and the Post-Apocalyptic Future. Both are harsh, wild frontiers where, as Sergio Leone noted, “life has no value.” They often feature a semi-nomadic wanderer engaged in shootouts, standoffs, and showdowns. Fallout: Lonestar brings these similarities forward as a central stylistic choice.

THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN

Adopting a similar plot, it employs a narrative of seven warriors coming together to defend a group of innocents from a larger threat. Fallout: Lonestar focuses on the larger questions posed by the film. The film is about many things, but centers on survivor's guilt, the measure of a man, and what, in the end, make a life worth living once you've survived. Yul Brynner was trying to show the end of the cowboy's life more realistically. The ride into the sunset never ends, the killing takes its toll, and when they die it's either by the gun or the bottle.

POLICE DRAMAS

While the American Western is well-seated in the collective imagination, it is not currently in the forefront of popular culture. Fallout, as a setting, requires past and future ties to create a complete picture. The police drama, or cop show, is a modern narrative style we use to bridge the gap from western to modern day. The police drama shares many thematic and narrative devices with the classic western, which makes connecting them that much easier.

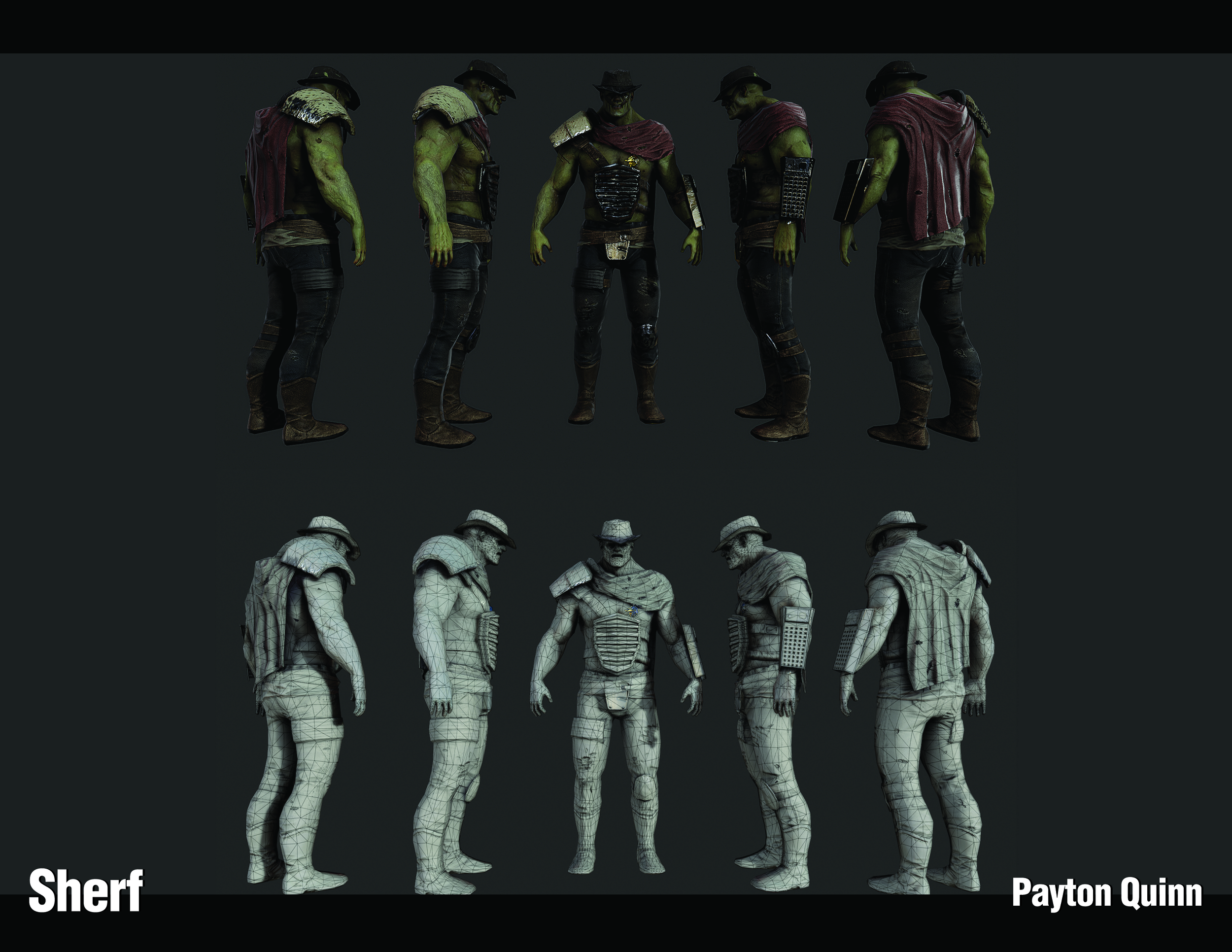

CONCEPT

While I developed the setting and primary narrative, I began reaching out to concept artists. Focusing on artists with a predisposition towards Fallout fan art, I was able to provide an opportunity for them to develop Fallout material rather than reproduce existing content.

Being able to put a visual stamp on the idea of Fallout: Lonestar was extremely useful and helped express our vision. Design documents and lengthy lore treatments are no match against TL;DR.

The key was to approach artists as a designer. I was able to use my background in Graphic Design to work with the artists in a common language. Providing my own middling concept art as a baseline would prove exceptionally effective. It's paramount to collaborate with Concept Artists versus simply submitting static requests.

Our concept artists vastly improved designs through their own interpretation. Keeping the requests broad and only specifying when necessary meant that there was always breathing room for artists to develop ideas.

SHELVED

While a great deal of pre-production and in-engine work was created, our implementation pipeline consisted of myself and fellow writer Max Supler, as we were the only ones willing to learn the difficult, and often obtuse Creation Kit. We’re very proud of what we were able to accomplish, but in the end, strictly financial concerns shelved the project. To this day, I believe the concept and direction of Fallout: Lonestar would have written a faithful and earnest chapter in the world of Fallout that fans would truly appreciate.